As is so often the case with ancestors, I don’t have letters or other artifacts to confirm Victor Eifert’s exact location at various times. However, I think there is enough circumstantial evidence to confirm that Victor did join the Union forces after the siege of Atlanta. With this and information from other sources, I hope to paint a picture of what his life may have been like during this time.

Drafted into the Army

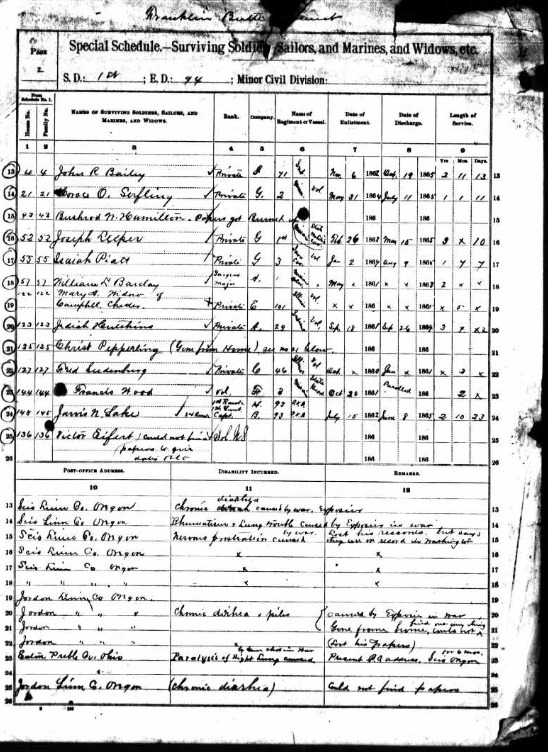

The first clue we have that Victor Eifert was a soldier in the Civil War are records of his drafting. U.S. Civil War Draft Registration Records tell us that Victor was subject to military duty beginning in June and July, 1863. Further records indicate that he was drafted into I Company of the 47th Regiment, Ohio Infantry.

Conscription was a controversial issue, particularly in that year. Men who were drafted were forced to serve in the army unless they could pay $300 or hire somebody to fight in their stead. Men like Victor Eifert and many other immigrants could not afford that. The draft would have also created hardship at home since Victor wouldn’t be present to work on his farm and support his family. We know there were two children at home while he was away.

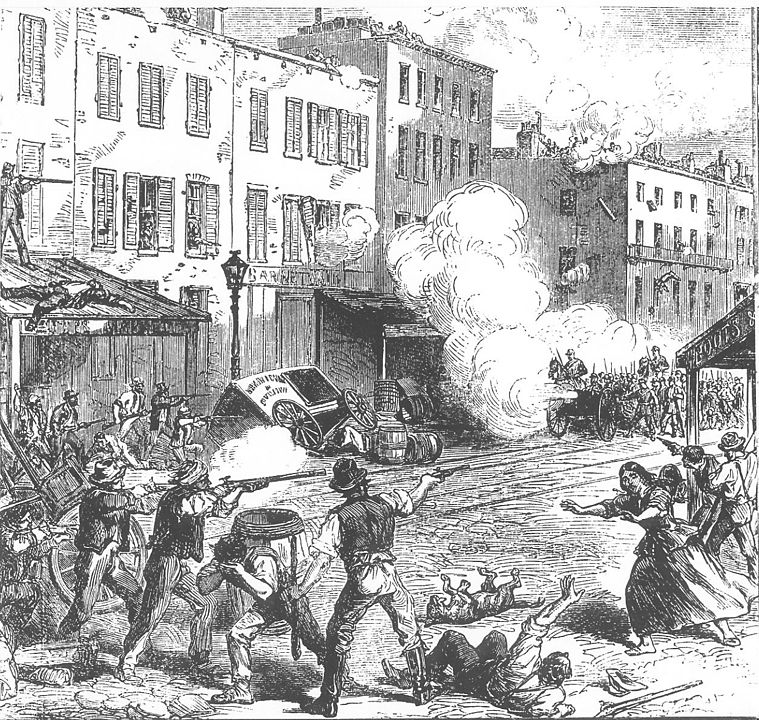

In several cities, conscription led to violent draft riots, as poor men rebelled against “a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight.” In New York, wealthy neighborhoods were ransacked, and several African Americans were lynched. The U.S. Army had to quell the rebellion by force.

Joining the Regiment

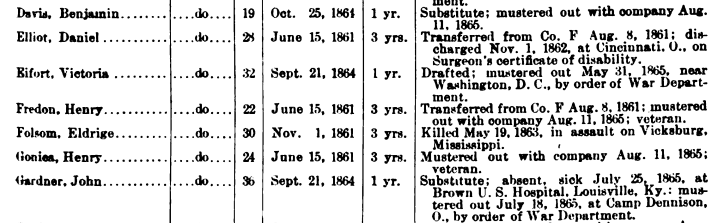

According to the official roster of the 47th Ohio Infantry, Victor Eifert entered the service on 21 Sep 1864.

We can make an educated guess on when Victor joined the rest of his regiment from the communications of its commanding officer, Col. August C. Parry. He wrote:

I started with the regiment from camp near Atlanta, Ga., on the 15th day of November, 1864, having received, a few days previous, about 400 drafted men and substitutes, who performed their duties in the subsequent campaign to my entire satisfaction, and better than I had reason to expect.[1]

Col. August C. Parry, 47th Ohio Infantry

In A History of the Forty-Seventh Regiment, Ohio Veteran Volunteer Infantry, soldier Joseph Saunier describes the arrival of a few hundred troops per day at Vinning Station, Georgia. On 7 Nov 1864, he wrote: “To-day, one hundred more recruits came to our regiment; they have the appearance of good sound men and no doubt when they are drilled they will make good soldiers.”[2]

As the new recruits arrived, the men of the regiment knew they would soon be moving out. Saunier notes that men were writing letters home as they knew the last train would depart on November 9th. On November 11th, the last trainload of recruits arrived, and the final train headed north departed.

Saunier writes:

In the afternoon we saw and watched the last train going north, and afterwards large fatigue parties were sent to tear up the railroad and pile up the ties and burn them, and thoroughly twisted the rails…Thus all the railroads around Atlanta were destroyed for many miles.[3]

Joseph saunier, 47th Ohio Infantry

When he joined the 47th Ohio, the regiment had been through fierce fighting. Prior to the Siege of Atlanta, where there were over 3,000 union casualties. They had taken a costly role in the Siege of Vicksburg, one of the lesser discussed but most important battles of the war.

Most recently, in August 1864, the regiment had fought at Jonesboro, Georgia, just south of Atlanta.

When the 47th Ohio began the war, it consisted of 830 men. Excluding the draftees like Victor, only 120 men were left by war’s end. The men that Pvt. Victor Eifert encountered outside of Atlanta had seen plenty of hard fighting.

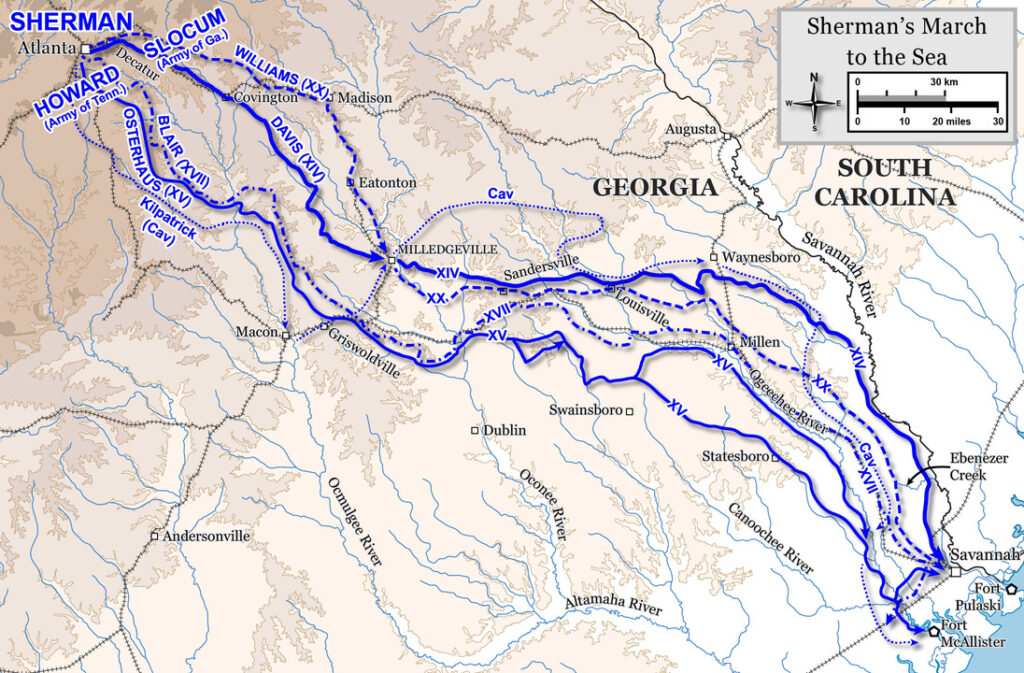

The March to the Sea

In broad terms, Sherman’s March to the Sea was totally unorthodox to military minds at the time. Sherman’s plan was to move swiftly, out past the lines of communication and supply, to take large swaths of territory. His corps were spread out, making it very difficult for the Confederates to know where he would attack next.

For Victor Eifert, this would have meant a lot of marching and brief rests. Joseph Saunier, also in the 47th Ohio, described the outset of the march:

The army is now cut off from all our friends at home. We were called this morning long before daylight to be ready to march, no one knows where; if the officers know they will not tell…The 47th with the brigade started on the grand march at 7 A.M., on the extreme right of the army. We leave Atlanta behind us smoldering and in ruins, the black smoke rising high in the air and hanging like a pall over the ruined city. We were cheery and marching quite rapidly, and the boy struck up the anthem, John Brown’s soul goes marching on, and other national airs.[4]

Joseph Saunier, 47th Ohio infantry

On their first day out of Atlanta, the regiment marched 16 miles. It’s clear that this took a toll on the new recruits, like Victor, who had not become accustomed to that much daily marching. On the second day, the men began at 6:15 am. Saunier writes, “Some of the boys helped some of the recruits carry their things, to help them along. The whole country is on fire to our left as far as we can see.”[5]

The 47th Ohio continued marching toward Savannah, foraging sweet potatoes and other vegetables as they went along. On many days they marched twenty to twenty-five miles, an arduous task. During the march, Victor would have encountered slaves, perhaps for the first time, who were joyful to see the Union army moving through.

One theme that stands out in Saunier’s account of the March is the utter devastation that the army marched through.

Our clothing is nearly all wet, but it will put out the fires which are raging from the right to the left wings; thousands of acres of pinewood are on fire, fences and everything in its path swept by fire, which is done by unprincipled men in both armies.[6]

Joseph Saunier, 47th Ohio Infantry

By 11 December, the Battle for Savannah had begun. The 47th Ohio would here see its only combat during the March to the Sea.

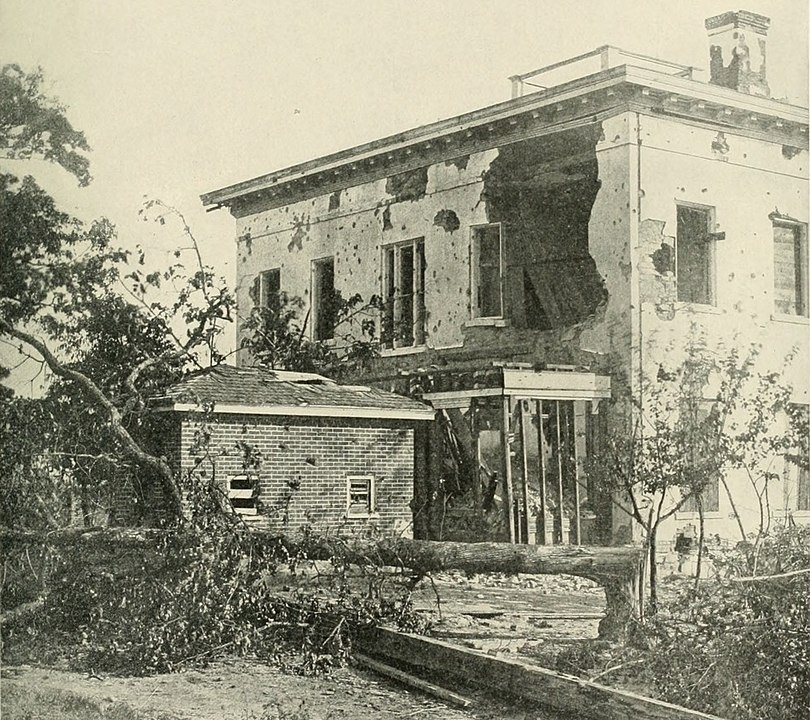

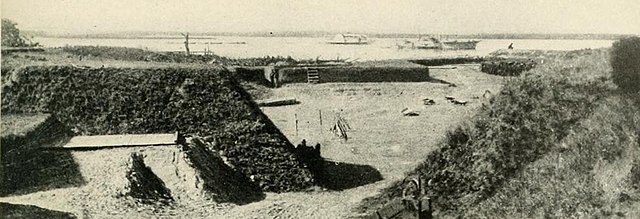

Battle of Fort McAllister

On 12 December, the division established a camp outside Ft. McAllister about twelve miles from Savannah. It’s worth noting how strange and different this country would have been for Victor Eifert. He had been born in Germany and lived in Ohio for his entire life to this point.

Gen. Hazen describes the atmosphere this way:

It was a scene of tropical beauty; the lemon, orange, and other plants, known to us only as exotics, were growing freely in the open air, and loading it with their fragrance. Never before or since have I been quartered in such a paradise.[7]

Gen. William Babcock Hazen

As they marched closer to their objective, Hazen notes:

Crowds of colored people came out to see the troops at every farm-house, all chattering at the top of their voices in a jargon like a mixture of French, English, and the clatter of blackbirds. They were the rice-field hands, and seemed to me a type of humanity as distinct as the gypsies.[8]

Gen. William Babcock Hazen

George Luber, a veteran of the 47th Ohio from Franklin, Ohio, described the battle in a 1898 article in the National Tribune:

The position of our regiment, the 47th Ohio, came to be the extreme left, near the river.

The bugle sounded the advance. We turned left flank and made our way around the stockade down to the river’s edge, right under the fort, where I expected every moment hand grenades thrown among us. We commenced climbing and it proved to be a much easier job than we had anticipated. Our flag went up as we did, coming somewhat left-oblique. It never went down, as is often stated.

As we got to the top of the works we found the Johnnies had already evacuated this part of the fort for us, and retreated to a farther-most corner, so we all made a rush and got on top of the center magazine, in order to control the whole place.

George Luber, 47th Ohio Infantry

Though the battle wasn’t much to write home about, the march itself is historically noteworthy. Saunier describes it this way:

In that eventful month we had broken up the connection between the Confederate forces east and west of Georgia by the destruction of over 200 miles of railroads; had consumed the available provisions in a territory 50 miles wide by 300 in length; had liberated a countless number of slaves and carried away 10,000 horses and mules; had destroyed one hundred million dollars worth of property; our herd of 5,000 cattle at the start had augmented to 10,000. Our total loss during the entire march was only 103 killed, 428 wounded and 278 missing.[9]

Joseph Saunier

South Carolina, Lincoln’s Assassination and The Grand Review

The 47th Ohio wasn’t finished marching once Savannah had fallen. Next began the far less well known but important Campaign of the Carolinas.

While there were some scraps between Union and Confederate forces, by this point the rebellion had been shattered. On 14 April 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Knowing that a peace treaty was close, Sherman tried to hide the news from the men, fearing it would spark revenge murders. We don’t know when Victor would have learned the news, but it would have caused quite a stir.

On 18 April, an armistice was signed and the fighting was over.

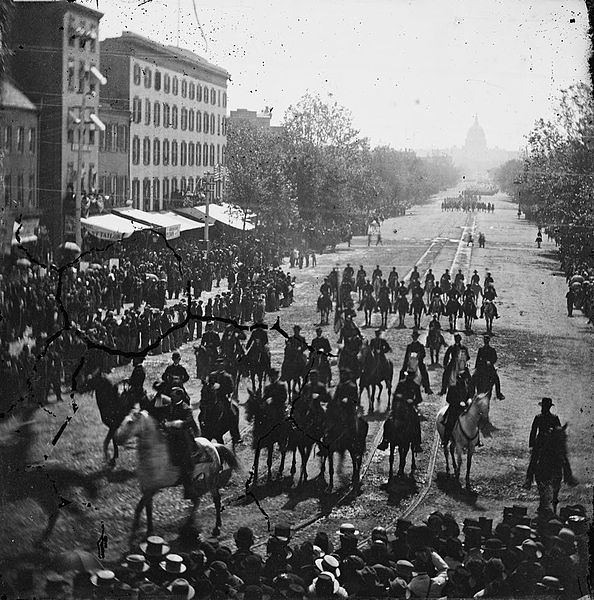

From I Company’s roster we know that Victor Eifert was mustered out on 31 May 1865 near Washington D.C. This means that if he was still with the company through all this time, Victor would have been present for the Grand Review of the Armies in Washington, DC.

The entire Union Army marched for review in front of Abraham Lincoln, his cabinet, and numerous government officials. In his book, Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American:

On the 23rd, the Eastern armies (the Army of the Potomac) marched in review through Washington, an endless column of troops well-clad and well-drilled, their ranks trim and spotless. Returning from the pageant Sherman, with his customary candor, declared: ‘It was magnificent. In dress, in soldierly appearance, in precision of alignment and marching we cannot beat those fellows.’ Then some one suggested that they should not attempt it but instead should be workmanlike and pass in review ‘as we went marching through Georgia.’

Sherman caught up the suggestion and next morning as the people of Washington watched the Grand Army of the West defile before their eyes they saw no glittering pageant, but instead an exhibition of virility. With uniforms travel-stained and patched, colors tattered and bullet riven, brigade after brigade passed with the elastic spring and freely swinging stride of athletes, each followed by its famous ‘bummers’ on laden mules ridden with rope and bridles. The most practically trained, physically fittest and most actively intelligent army that the world had seen.

B.H. Liddell Hart in Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American

Aftermath

As I mentioned at the beginning of the article, we don’t have photos or letters from Victor Eifert during this time. I’ve painted a picture of what he might have seen throughout his time with the 47th Ohio, but all we have for certain are records.

On his pension record, Victor has a recorded disability for “diarrhea.” While that may seem odd to us, dysentery was one of the biggest killers of the Civil War. There were over 1.6 million reported cases of diarrhea, with one doctor claiming more soldiers were killed from disease than battle. This was a result of malnutrition throughout the war.

Victor’s wife Matilda would have been overjoyed to see Victor home again with her and two children. Records indicate he returned to his farm in Ohio, until moving north to Minnesota, a story that deserves an article of its own.

Without having any of his correspondence, it’s impossible to know how Victor was impacted by his time in the Civil War. But we can be certain it did play some role in his life. How could such an extended exposure to death and destruction not leave some imprint?

A Note on Civil War Genealogy

If you’re reading this and wondering how to find a relative who fought in the American Civil War, the National Park Service has a Civil War Soldier database you can search. Keep in mind that if you have a more common name, there may be more than one entry and you’ll have to do some further research.

Ancestry features Civil War pension and recruitment records, which are quite helpful.

To most effectively paint this sort of picture, do a Google search for the regiment and company (e.g. 47th Ohio Infantry Co. I). Often the unit will have been mentioned in newspapers, and its commanders may have written memoirs.

Please contact me with any questions you may have.

[1] https://www.ohiocivilwarcentral.com/entry.php?rec=1238

[2] A History of the Forty-Seventh Regiment O.V.V.I, 346

[3] A History of the Forty-Seventh Regiment O.V.V.I, 347

[4] A History of the Forty-Seventh Regiment O.V.V.I, 351

[5] A History of the Forty-Seventh Regiment O.V.V.I, 352

[6] A History of the Forty-Seventh Regiment O.V.V.I, 360

[7] A Life of Military Service, 330

[8] Ibid.,331

[9] A History of the Forty-Seventh Regiment O.V.V.I, 366

Leave a Reply