Hesse, 1833. People were looking for a way out. Emigration to America was a known option. Rumors circulated about the possibility of emigrating to Algeria, where the French had just thrown out the Ottomans. Reports of immigration to Brazil seemed promising. But there was a problem.

The people didn’t know what they were getting into.

Families were selling all their belongings quickly and at a discount, not careful about what they might need. The city of Bremen reported that immigrants arrived without a trip booked and ended up destitute, spending what money they’d bought to survive. Penniless people were asking for government assistance to return home.

The authorities knew their constitution prohibited them from preventing emigration, but they needed to educate the people about the perils of emigrating to the United States, and how to avoid them.

To that end, the Hessian Ministry of the Interior ordered that the following article, “Well-Intentioned Counsel,” be distributed. It was written by the Leaders of the German Society in New York.

The article covers some important points that your German ancestors would have had to consider:

- The realities of life as an immigrant in the U.S.

- How to survive the journey across the Atlantic

- How to navigate the culture of New York City

- How much travel will cost and what to bring

So without further ado, here’s the article “Well-Intentioned Counsel of the Leaders of the German Society in New York to Germans who Intend to Emigrate to the United States of North America.”

———

The undersigned leaders of the German Society in New York have become convinced that the greater part of the numerous immigrants from Germany to the United States lack a proper understanding of what they should expect here, and that the delusion in which most find themselves not only causes them harm, but also leads many, perhaps even in their later years, to give up a peaceful, though modest, life in their homeland, in order to seek fortune abroad. This not only prevents them, once they have arrived, from making use of appropriate means for their advancement, but it also causes them to fall into misfortune.

The desire of the Society to ward off this evil has prompted its leaders to provide a truthful description of the condition of German immigrants in this land, and to accompany it with some useful advice for the latter.

Those immigrants, of whom we are speaking here, can be divided into two main groups and three subgroups: namely, into the wealthy and the poor; into tradesmen, laborers, and landowners. By the wealthy class we mean those who, at home, owned a small property or pursued a craft or live from farming. If these people, misled by the alluring writings that fall into their hands through the selfishness of others, then decide to leave their homeland with their families, the first consequence is that the business they have pursued up to that point must be abandoned, in order to make preparations for the impending journey.

The family’s expenses immediately increase, and of course are further increased by the necessary travel arrangements. The property and the immovable fields and agricultural implements are sold, usually for less than their true value, since they must be sold quickly, and usually several families leave a district together, thereby increasing the number of sellers, while the number of buyers becomes fewer.

Now the journey begins, which in most cases costs far more than expected, since the travel and unavoidable delays of a family often extend their stay in one place longer than anticipated; furthermore, the money brought along must, as one travels through various countries and provinces, be exchanged several times, and each time the money changers profit from the ignorance of the exchangers.

At the port of embarkation, the agents of the ships try to extract the highest possible fare from the travelers. In order to save this expense, they often accept a very poor diet on board and sign up for a crossing which, even when favorable, counts for about 30 days; but when the voyage, as is often the case, lasts 60 days or more, then the passengers are compelled to buy additional provisions on board, and must often pay dearly for them. With a very limited capital, they will not be able to remain in the new land long enough to reap the fruits of their sacrifices and the hardships they have endured.

We will assume here that New York is the place where the newcomer lands, let us imagine him as a craftsman, since we will discuss the situation of farmers and day laborers later.

Unfamiliar with the language and the customs of the country, he feels lost in this great and expansive city; for New York, with a population of more than 200,000, is predominantly a trading town, with the usual proportion of sailors, artists, craftsmen, laborers, etc., who in general speak nothing but English.

The foreigner cannot make himself understood by anyone; finally, after some time, he meets a few Germans on board, and he is delighted to hear himself addressed in his familiar mother tongue. Unfortunately, however, there are among these people interpreters and intermediaries who take advantage of the ignorant, seeking to profit unlawfully from them—and the newcomer therefore has good reason to be cautious of them.

There are also innkeepers who lure arrivals into their houses, where they try by all kinds of false pretenses to keep them as long as possible, until every last penny is consumed; then they either turn them out into the street or send them on to the German Society.

If the newcomers still have money left, perhaps work is offered to them, but often such innkeepers persuade them that the wages are good, while in fact they pay even a craftsman only a miserable wage, and keep for themselves the greater part of the pay.

In both cases, the newcomers must add from their small reserves; and if they then discover that they have been deceived, they become disheartened, and grief, together with the effects of the new climate, often drives them into illness. They then need help from strangers, which would not have been necessary if they had acted more prudently from the beginning and had proceeded with proper care.

If such misfortune befalls the father of a large family, his situation becomes truly pitiable. Yet rarely does an improvement begin just then, because the immigrant, once he has come to a correct judgment of his situation, can also act more sensibly. He either goes inland, to a region where many Germans have already settled, or he takes moderately paid work and strives, through diligence and frugality, to acquire something, so that he may later establish himself here or in some other place.

It should be made known to the German craftsman that in this country there are no guild privileges. Thus anyone can work in whatever trade or field he wishes. The consequence is an extraordinarily strong competition among workers, so that many things have come to be made here either better or at least in a simpler and cheaper way than in Germany.

The craftsman arriving from there is therefore at first not only disadvantaged by his ignorance of the language of the country, but also by the way in which his work methods differ from those of the locals. Both difficulties, however, are not insurmountable, and once a capable and diligent craftsman has overcome them, he can find a good livelihood here in the country.

If such a craftsman, after careful consideration of all the difficulties he must overcome, nevertheless decides to move with his family to this country, it may indeed offer him, despite his relatively small population in proportion to its size, certain advantages.

Therefore, the following well-intentioned counsel is recommended to him for the better attainment of his purpose:

He must not only consider his cash reserves, but also, in the sale of his property and other possessions, act with the greatest caution. Rather than sell these things badly at an inopportune time, he should wait for a more favorable moment, but in the meantime devote himself with redoubled diligence to his trade, and lead a frugal life; partly in order, if possible, to increase his means, and partly to accustom his family to the deprivations which they may later have to endure for a time.

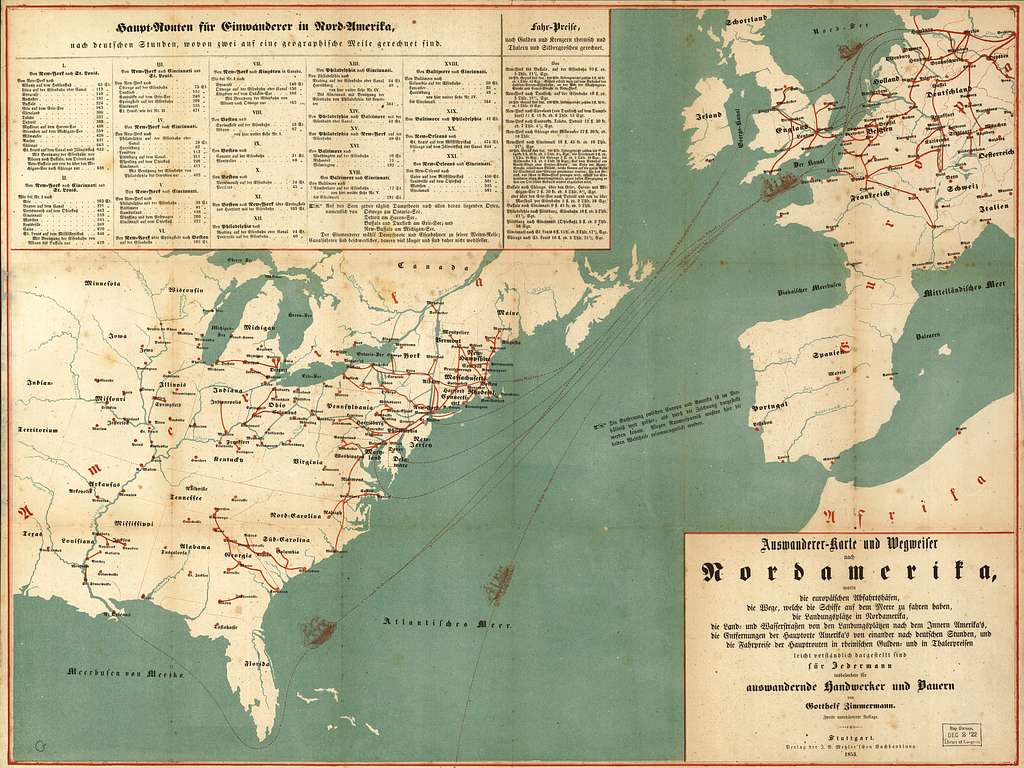

If he has converted his property into money, he must then, after careful inquiry, calculate his travel expenses, for which purpose the tables attached to this small pamphlet can serve as a guide. To the sum deemed absolutely necessary, he should add at least one quarter more, so that he does not find himself in distress on the way.

And before departure, he should exchange his money into the various coins that he will need on the journey, with the help of an honest and trustworthy man, known to him as such. To avoid being cheated by speculators, he should bring as few goods with him as possible, only what is necessary for the trip, and as provisions only the items listed here, which he can purchase in the seaport where he embarks.

For the part of his assets that will remain, he should either exchange them into French gold or silver coins, or entrust them with a reputable and reliable banker, perhaps through the agent of the packet ships, who will give him a letter of credit on a banker in the place of arrival, from whom he can withdraw the money once he has arrived.

The latter option, however, carries no small risk of being robbed on the way or immediately upon arrival in America, as has already happened to many immigrants. Therefore, when he arrives, he should not bind himself to a long lease, but immediately seek work, even if at first for a low wage.

In most cases, at least the newcomer an at least immediately earn his living; and once he has become acquainted with the language and the methods of work, he can make greater demands.

If, however, as often happens, many immigrants from England, France, and other countries arrive at the same time, and he cannot find work right away, then he must promptly move on—either into the interior of Pennsylvania or into the state of Ohio, where many German settlements are, and where his prospects for work are therefore much greater.

But even in other parts of this country there are numerous German settlements to which the immigrant may turn. The journey to some of these regions is indeed long, but since they are connected to the main routes of communication by steamboats and canals, it is neither overly difficult nor costly.

Along the way, however, he will often encounter people who, being lazy and idle themselves, can get nowhere, and who, having lost courage, turn back halfway and try to persuade others to do the same. He must not let himself be deceived by them; for we are convinced that the diligent and skillful craftsman will always find a place in the interior of the country where his work will provide him and his family with a good livelihood.

Different customs and habits may initially seem strange to him, and perhaps he must forego some comforts to which he had become accustomed in the homeland; but he can live without worry, if only he is diligent and frugal.

The larger the sum of money he has set aside before his departure, the easier and safer his progress will be; but even with little, he can make his way if he knows how to spend it wisely. He must, however, do everything possible not to waste his money on unnecessary things.

It is also highly recommended that he, even during the journey inland, keep a small reserve frugally hidden, which may serve him in case of need; for many, having been careless, have been robbed.

Wealthy farmers, once they have arrived here, should of course proceed in the same way as the craftsmen. After their arrival, they should go inland as quickly as possible, by ship if they can, and either move into Pennsylvania via New Brunswick to Easton and from there further inland, or else toward Ohio via Albany, Buffalo, etc., until they reach an area where they can purchase land cheaply, and where work on already-settled farmland is offered to them.

In some cases, they would do well not to buy land immediately, since in this way they can first become acquainted with the American methods of farming, which in several respects differ from the German, and later invest their money with greater knowledge to better advantage.

We now come to the poorer class, which includes most: laborers or day workers, though some are also craftsmen. For this poorer class, it is generally the case that unmarried, strong young men and women emigrate.

If such young men immediately take up work as day laborers in the countryside or on road construction upon their arrival, provided they are not craftsmen or cannot find such employment, and if the young women hire themselves out as servants, then they can at least earn their livelihood at first.

After they have learned some of the language and the manner of work, and if they combine frugality with diligence, they may then hope to acquire a better future. Should they wish, they can later assist the children or elderly parents whom they left behind, so that they may either support them from here, or, if possible, bring them over as well.

But elderly people, the sick, and poor families with many children ought to be dissuaded by humane considerations from emigrating, for emigration for them is nothing but misery.

To all immigrants we advise, when dealing with the ship’s captain who brings them here, that each family conclude a proper written contract with him. In it the captain is obliged to provide them with sufficient fuel and water for cooking their meals, and also sufficient water for drinking. They should insist on receiving one gallon of fresh water per person per day.

They should also stipulate in writing that the passage fee includes the hospital fees or other municipal charges that must be paid upon arrival here.

They must arrange their departure so that they arrive during the warmer season, and therefore should not depart before the beginning of March, nor later than the end of July.

If they arrive shortly before or during the winter here, their situation is much worse in every respect.

We also warn them not to engage in disputes with each other on board the ship, and especially not with the crew, and least of all with the captain or the steersman. Toward the latter they must always behave with the greatest politeness and respect.

If they believe they have important complaints to make, they should bring them up modestly with the captain. If they believe themselves seriously wronged by the captain during the voyage, they must wait until they reach their destination port to lodge their complaint and seek justice; for on board the ship, the captain is by law the highest authority; but for any misuse of this authority, he is accountable after the voyage has ended.

We close these words, directed to our countrymen, with the heartfelt request that none may step forward to emigrate here unless he is determined and capable of earning, through industry and a respectable way of life, the love and esteem of this country’s citizens. Without this, no one may flatter himself with hopes of a secure future.

For the idler and the drunkard, there is here, as everywhere, only contempt and misery.

The bad conduct of a foreigner always attracts more attention, and brings not only certain punishment upon himself, but also disgrace and dishonor upon the nation to which he belongs.

Signed:

PHILIP HONE, President

CASPAR MEIER, Vice President,

also Consul of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen

C. W. FABER, Treasurer,

also Consul of the Electorate of Hesse

GEORGE MEYER, Secretary

GEORGE ARCULARIUS

DAVID LYDIG

JACOB LORILLARD

J. W. SCHMIDT,

Royal Prussian Consul, also Consul of the Free Hanseatic City of Hamburg

D. B. DASH

CHARLES GRAEBE

F. S. SCHLESINGER

New York, January 1, 1833

Estimate of Travel Costs, etc.

After careful inquiries, we believe we can recommend the following guidelines as a rule of thumb for calculating travel expenses:

Travel costs within Germany, on foot or by freight wagon, including board:

- For adults, each 1 Thaler per Prussian mile.

- For children, each ⅓ Thaler per Prussian mile.

From the French border to Havre, including board:

- For adults, 50 Francs.

- For children, 35 Francs.

For passage from Havre, adults pay (without provisions) 80 to 150 Francs per person. Children under 10 years half price.

The packet ships usually charge the highest price, but they are also the best, and passengers are usually treated best on them.

Purchase of provisions is estimated at about 40 Francs per person, the same for children as for adults.

The passage from Bremen or Hamburg usually includes provisions, etc., and costs about 30 to 40 Spanish Thalers.

We recommend that emigrants in these ports book passage with German ships that sail regularly to here, and that in the contract they stipulate the sailors’ rations.

List of items to bring.

The emigrants should take care to provide themselves with:

- Woolen clothing for one year.

- Linen and underwear, as their means allow, a full set of clothing.

- Women’s clothing, sufficient for the journey and several months’ stay here, since the style of clothing here is quite different.

- Shoes and boots in good supply.

Above all, old and worn-out clothing should be left behind on the journey, especially at sea; but on board one should be as clean as possible, frequently changing underwear, since this contributes much to health.

As for bedding and pillows, they should in general bring only what is absolutely necessary for the journey.

Beds, as well as furniture, wagons, farming implements, and tools, should not be brought along, since transport is expensive and makes the journey burdensome. All these items, once a family has settled down, can be acquired just as well and often more suitably in this country.

List of preserved foodstuffs to bring

- 80 pounds salted beef.

- 100 pounds hard bread or ship’s biscuit.

- 2 bushels of potatoes.

- 25 pounds rice.

- 25 pounds flour.

- 1 bushel peas or beans.

- 20 pounds sugar.

- 1 pound tea.

- 3 to 4 pounds coffee.

For the first couple of days, one can take along some fresh meat and vegetables, if circumstances allow, and also wine and other drinks, as one’s means permit. But in this regard moderation and frugality are strongly recommended.

The above rations apply for both adults and children, per person; for children sometimes eat even more than adults while on board ship. For a family of 8 persons, however, 6 rations will be sufficient.

The emigrants do best if, in France, several families together purchase as much as possible, so that they can benefit from the wholesale discount, by which they will obtain the goods at cheaper prices.

Leave a Reply