In a previous article, I provided a selected translation from a book by Fr. Ferdinand Giessler about the French invasion of Baden in 1796. Now, we have another account of those events from the Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Beförderung der Geschichtes-, Altertums- und Volkskunde von Freiburg, or the Journal of the Society for the Promotion of the History, Antiquity and Folklore of Freiburg, published in 1925.

If you have ancestors from Frieburg im Breisgau and the towns along the Höllental, this article will help paint a picture of what their lives may have been like during the Napoleonic wars. Forced quartering of troops, robbery, looting and other mistreatment were something they would have likely experienced.

What follows is the translation:

__

Local history and universal history constantly touch and permeate each other. Major world events have an impact on the destinies of landscapes and cities and even on the lives of individuals. But not everywhere to the same extent. Places close to the borders of states are more strongly involved than others in the struggles of nations, and more than elsewhere the great course of history is reflected in their past.

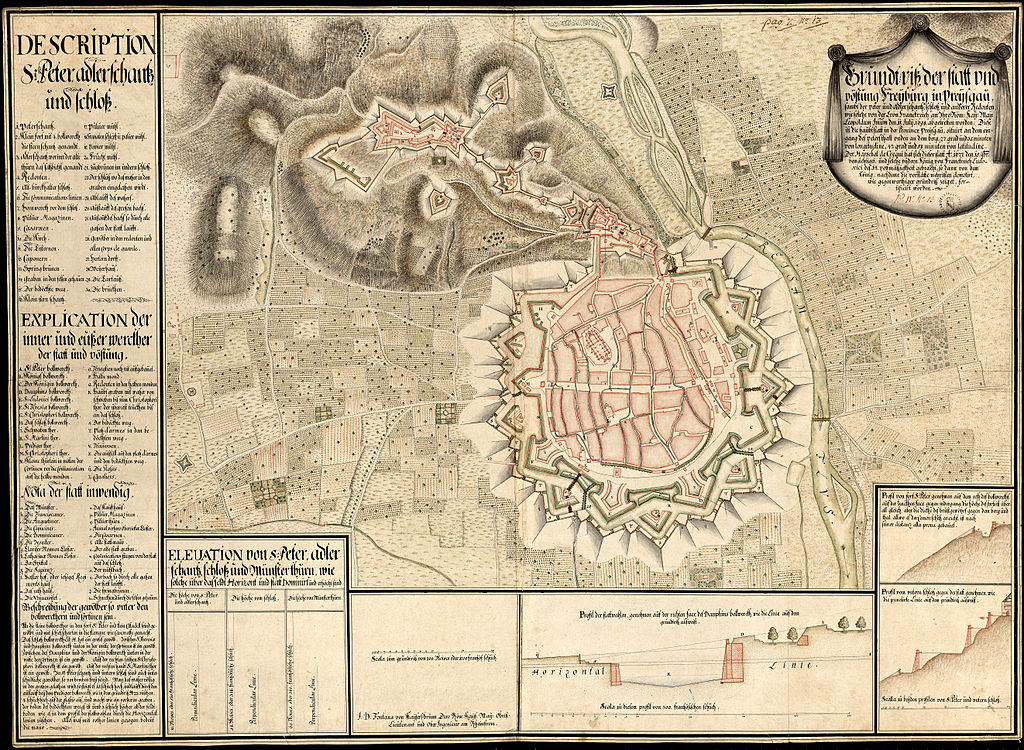

As long as Freiburg was still a fortress, it was often and fiercely contested in the battles between Germany and France. Repeatedly, and once even for two decades, it was under French rule. But even after it became an open country town in the middle of the 18th century, it was severely affected by the hardships of the times. The Rhine flowed at such a short distance, and on the other side of the Rhine was French territory. And when the French came over conquering and plundering in the Revolutionary Wars, albeit in the name of their new freedom, Freiburg also lay in their path, and the history of the town tells of enemy marches and occupations, of contributions and pillaging and violence of all kinds.

The comings and goings of the French in 1796 were truly dramatic. For a quarter of a year, Freiburg had to endure the French occupation, which only disappeared again after France’s military defeat. The fate of the enemy army and thus of the entire campaign was decided in the immediate vicinity; at that time, the mountain road of the Höllental had attained world-historical significance; and for the inhabitants of Freiburg, the tension was all the greater because their own fate depended on the outcome of the fighting.

This episode, namely the occupation of Freiburg by the French in 1796 and the unexpected solution to the strategic problems, will form the subject of the following study. A period of a few months in which everything unfolded, and at the end, within a few days, the final surprising turn of events took place.

While Bonaparte began his victorious career in Italy, the campaign of 1796 brought the French in Germany severe disappointments. Two separate armies under two different commanders appeared, the Sambre-Meuse army, which crossed the lower Rhein under Jourdan, and the Rhine and Moselle army under Moreau. On the night of June 23-24, the latter won the crossing over the Rhine at Strasbourg, occupied Kehl as a bridgehead, fought its way over the mountains to Swabia and Bavaria, and also expanded southwards into the Rhine valley. Duke Karl, as commander of the entire Austrian forces, was forced to retreat and decides to give Moreau and his 50,000 men free rein in southern Germany for the time being, leaving only the most necessary troops behind.

He joined forces with General Wartensleben, who was operating against Jourdan, and defeated Jourdan at Amberg and Würzburg in August and September. One opponent was defeated, and Jourdan had to return across the Rhine. And now Moreau’s position in southern Germany, which had advanced as far as Bavaria, had also become untenable. He also decided to retreat and carried it out with some skill. But the difficulties grew. On October 1, the situation of the Rhine-Moselle Army seemed almost desperate. It was surrounded and besieged on all sides by Austrian troops. After receiving a report from Moreau on October 1st, the Parisian government thought it hardly possible that the commander would succeed in getting his army through the Black Forest and across the Rhine. In two letters dated October 11, the Directorate implored him not to expose the troops under his command to any danger. It even authorized him to cross into nearby Swiss territory if circumstances required it.

The French envoy Barthelemy had already been instructed to prepare the cantonal authorities for the arrival of the French and to give assurances that all orders from the Swiss authorities would be scrupulously followed. “What a disgrace it would have been for the leader of an army that has always been victorious,” wrote Marshal Saint-Cyr, “if he had decided to resort to this means!”

Instead, on October 2, Moreau succeeded in delivering a fortunate retreat battle to the Austrian General Latour, who was following him, which brought him relief. The most difficult task awaited him, however, when it came to winning the crossing over the Black Forest and clearing the way to Kehl, from where he had come.

But before we continue to follow the fate of the beleaguered French commander and his army, let us look back at events that have taken place away from the main theaters of war since the French appeared on the western slopes of the Black Forest, in Freiburg.

Part of Moreau’s army had withdrawn to the south, up the Rhine valley. They were not allowed to spread out here without a fight. The volunteers from the countryside and 1,000 Fribourg citizens fought alongside the Austrian troops. Baron von Summerau, the president of the province, had issued a circular and the city council had distributed it, “calling on the people to unite in the present danger and to defend the beloved fatherland against the common enemy”. In a battle near Wagenstadt, the 1000 performed “miracles of bravery”, as it says in the diary of the cathedral priest Bernhard Galura. Nevertheless, the advance of the French could not be stopped. On July 15, the government authorities issued an admonition to their officials that, as the French troops were expected to take possession of the Breisgau region, they should remain in their positions, obey the victor and prevent their subjects from engaging in hostilities and unrest, lest “ineffective nonsense” lead to disaster. The council, however, ordered those who had followed the storming party to beat the drums and deliver their weapons and ammunition to the council courtyard and to remain calm during the French troops’ stay in the city.

Two days later, on 17 July, a French officer was the first to appear, and an announcement by the magistrate sought to reassure the people by informing them that “Antoine Jarre, lieutenant of the VIII. Hussar Regiment of the estimable French Republic”, was the first to arrive in Freiburg and declared that he was coming as a friend and that the French would protect property and people, “so that we are completely reassured by this assurance”. Nobody believed in the truth of such assurances. “The people were sad and dejected”, Galura’s diary says. And yet the falsehood of this first declaration is far surpassed by a letter that General Mengaud addressed to the mayor and the city councilors when he took command of Fribourg and Breisgau on August 6. It contains, in classic formulation, the well-known phrases of revolutionary propaganda about the struggle of the French people against the enemies of the human race who want to destroy freedom, and about their friendship for all like-minded people. The letter was published in a German translation by order of the Council for general reassurance. But the characteristic French text also deserves publication. It reads:

Gentlemen,

I was delighted to receive the command of Freiburg and Breisgau. I am convinced that your good intentions, together with mine, will be sufficient to maintain peace and confidence in our city. Such is the wish of the French government.

We had been portrayed in your eyes as a nation hostile to all peoples. By proving the contrary, we will force you to esteem us.

Your persons, your property, your worship will be respected.

If the misfortune of war weighs on you, if a few individuals may have forgotten their duties, forgive them, and believe that the French nation will never share their wrongs.

The French people did not attack you; they pursued the enemies of mankind who wanted to destroy freedom.

If our victorious armies are scouring the lands of Germany, it is to bring peace to Europe.

Rest assured, Gentlemen, the French Republicans are and will remain your true friends.

However, Mengaud’s letter is best illustrated by the actions of his subordinates. We will attempt a brief description.

There is currently no information on the exact number of occupying troops entering Freiburg, but their numbers must have been considerable. The men were quartered in the barracks, the officers initially in the houses of non-citizens. However, these quarters were soon no longer sufficient, and the houses of wealthy citizens also had to be left to the officers, and space had to be found elsewhere for the troops.

Not much was heard in the city about the looting, violence and abuse that plagued the country. However, the landowners were demanded to give up their goods for the needs of the French officers and men. And as the businessmen were not sure whether they could expect to be paid, they preferred to take their goods away. The French general command now issued an order, under threat of the most severe coercive measures, to bring back the removed goods immediately and keep them ready for the French. Instead of payment, however, the merchants were explicitly ordered to pay the state treasury. The aggrieved merchants now sent a petition to the city and demanded payment, explaining that they had prevented general looting through their willingness. The city rejected them and recommended that they turn to the lords of the manor.

Occasionally one also hears of unauthorized extortion by French soldiers, which are of course an embarrassment to the command itself and are punished by proclamation.

The sacrifices imposed on the city in the form of rights were all the more oppressive. Several French officials arrived, whose main task was to extract as much money and goods as seemed possible from the unfortunate town. The most unpleasant of these guests was a certain Parcus, who is described as the Director General of the Revenues of the Conquered Lands on the right bank of the Rhine. He threateningly demanded that all taxes paid to date should henceforth be paid to France. According to one of his appeals, the French government is far from treating you with hostility, which it has the right to do, but it demands loyalty and obedience. “Do not allow yourselves to be seduced into disobedience, deceit and disloyalty by the dangerous ploys of selfish villains and fanatical cameleons”. The government of the free French people is magnanimous and just “but also strict against impostors who reward their magnanimity with shameful ingratitude”.

It was the same Parcus who imposed the enormously high war contribution on the city and countryside. The sums demanded from the Breisgau abbeys, the knighthood and the Abel, the citizens and farmers, the parishes, benefactors and church establishments amounted to a total of 1300,000 livres. And the requisitions, which are recorded on long lists, were certainly no less oppressive. And there was no shortage of the looting of art treasures so often carried out by the Revolution’s military leaders. Baldung’s painting “The Flight into Egypt” and Holbein’s paintings in the university chapel in the cathedral, among others, had to be handed over to the French.

Another type of extortion appears more harmless and not without humor. It takes the form of forced gifts. We hear of French officials who have to be given new clothes at the city’s expense. A “Commissaire de Guerre”, in a polite letter dated the 1st of Fructidor in the fourth year of the Republic (August 18, 1796), expresses his heartfelt thanks to the magistrate and the city of Fribourg for a gift of 5 cubits of super cloth that he received and 3 cubits of coarser cloth for his secretary. Unfortunately, he himself had to leave the city soon, but his successor would be no less worthy of their kindness than he himself. If the city would also supply him with the fabric for a new suit, of the same fine quality and from the same merchant, it would not only oblige him, but also the clerk, his comrade, to double thanks.

And it also seems like an almost endearing little expression when, on the 3rd of Thermidor (July 21), the commander wishes to give a ball in the count’s Althaus house, where he lives, and the magistrate is now asked in kind words to suggest to 12 capable musicians to appear at this celebration. “One is counting on this number,” the letter concludes, “in order to obtain a suitable orchestra. – Salut et fraternité!”

* * *

The pressure of the French occupation weighed heavily on the city of Freiburg. It lasted for almost a quarter of a year, until the military situation had fundamentally changed and it was impossible for the French troops to remain on the right bank of the Rhine. So we turn back to the events on the battlefield, to the final act in the history of the German campaign of 1796.

After the victorious battle at Biberach, Moreau’s army continued its march to the west in several columns. Smaller battles, which were fought with Austrian troops near Billingen and Rottweil, did not change the military situation much. The real difficulties only began when the French entered the Black Forest region. Opinions differed among the generals as to what measures should be taken and in which direction the march should continue.

We hear of a dramatic war council that Moreau held with his subordinate generals Desaix and Saint-Cyr at Donaueschingen; it must have been on October 9 or 10. Moreau had to reach the Rhine plain at all costs and his particular objective was the bridgehead of Kehl, which was in French possession but already surrounded by the Duke’s troops. The best and most commonly used route there led down through the Kinzig valley and via Offenburg. Now, however, Desaix declared to Moreau in great pain that he did not feel strong enough with his troops above the Kinzig valley to force his way into the valley. Under these circumstances, Moreau thought he could only consider the route around the southern edge of the mountains, towards Hünigen. It was Saint-Cyr who made the decision to take the shortest route into the Rhine valley, namely the one through the Höllental and via Freiburg.

Never before in history had a large army passed through the Höllental, and a few decades earlier this would have been impossible due to the narrowness and difficult passability of the valley. And even if we assume today that a certain amount of mountain traffic has always passed through the Höllental valley from ancient times, and that it was even crossed by armed troops on several occasions during the Peasants’ War and the Thirty Years’ War, it was only in the 18th century, particularly between 1755 and 1770, that the actual Höllental road was built and opened to mountain traffic. And when the construction was completed, the young emperor’s daughter Marie Antoinette soon drove through the new road on her way to France.

In the war council of the generals at Donauschingen, Saint-Cyr’s proposal was initially received with some dismay. None of those present were familiar with the nature of this road, and the Val d’Enfer was imagined to be something terrible. It was recalled that Marshal Villars had also shied away from marching through the Höllental valley on his expedition through southern Germany in 1707, and was probably unaware that the new road had not even existed at the time. However, all doubts disappeared when Saint-Cyr offered to take his own corps on the march through the Höllental and towards Freiburg.

Moreau agreed. It was decided to push the entire French army, first the center under Saint-Cyr, then, following him, the two wings under Desaix and Ferino, through the Höllental, towards Freiburg, and to win the Rhine valley here. This would establish a link with France, namely via Breisach, which was in French hands, and would also make it possible to march northwards in open terrain to dispose of Kehl.

The probability of success lay in the suddenness of the decision, in the speed of execution, in the surprise of the opponent. This succeeded perfectly. A sufficient Austrian force to stop the French march through the Höllental was not on hand and could not be mustered in the short time available. All the less so now that the clever and prudent execution of the French plan was worthy of the boldness of the decision.

But what did the Austrian army command decide when it received the news that the enemy was appearing where it was least expected, that it wanted to force its army of, say, 40,000 men through the narrow mountain road, which no one had seriously considered using for this purpose? In his own account of the campaign of 1796, the supreme commander, the excellent Archduke Charles, faithfully and modestly listed the mistakes he had made in the conduct of the campaign of 1796. He said that after overcoming the Sambre and Maass armies, he had left too many troops, namely 32,000 men, on the Lower Rhine. 20000 would have been enough, and the remaining 12000 would have given him an even more decisive overweight on the Upper Rhine. Furthermore, he should have immediately marched to the upper Neckar and united with his lower generals there. This would have made it more difficult for the enemy to enter the mountains and move there. Thirdly, after the operation on the Lower Rhine had been completed, he should have personally moved to the now decisive location, i.e. the area of the Danube and the upper Neckar, and taken command there.

However, all of this lies before the point in time that we are discussing. Archduke Karl did not say that, as things now stood, Moreau’s march through the Höllental could have been prevented, and for all his tendency to self-reproach, he did not see any fault of his own in the fact that this march was not prevented. In fact, he did not even try. When he received the message on October 12 that the enemy had entered Neustadt, it was too late. The Archduke now gave the following instruction: If the troops advancing from Neustadt into the Höllental were the bulk of the enemy army, General Latour (to whom the instruction was given) was to follow General Petrasch, who was already on the march, with his entire right wing. They are to join him, the Archduke, who is in Renchen, either through the (Simonswälder and) Elzach valleys or through the Kinzig valley, without losing any time, so that he can get air to keep the enemy away from Kehl. Of the troops of Field Marshal Lieutenant Frelich to the south, however, a smaller detachment – it is expressly stated that it is to be only a few battalions – is to follow the enemy through the Höllental valley and worry him there, while the larger part, “a strong detachment”, is to pursue the enemy on his way through the forest towns. And finally, the meaning of the whole letter is summarized once again: it is important to bring as large a part of the army as possible into the Rhine valley between Gengenbach and Kenzingen as quickly as possible in order to cut off the enemy from the connection with Kehl.

Thus Moreau’s army was able to march from Neustadt through the Höllental valley with ease, without being strongly harassed by the Austrians. It was done with great care and energy. From the point (approximately from Hinterzarten) where the terrain narrowed, Saint-Cyr had to advance with his center, led by Girard, while the two wings moved over the heights on the right and left, over Hohle Graben – St. Märgen and over Alpersbach, in order to make any attack on the troops marching down in the valley impossible. The small Austrian detachment that the French under Lieutenant-Colonel d’Aspre found in the Höllental could not hold out for long. The armed peasants with him soon abandoned him and the posts he had set up on the heights near St. Märgen were “routed”. On the sides, he found himself outflanked by the enemy and hard pressed by Saint-Cyr’s troops advancing through the Höllental. Even a detachment sent from Offenburg to slow Saint Cyr “in the cave” was unable to help and hardly went into action. According to the report of one of his officers, Major Croll, d’Aspre was “forced out” of the Höllental via Himmelreich. Still “from hell”, he had sent the Archduke a report of the first appearance of the French on the morning of October 11 and urgently requested cavalry reinforcements. At 9 o’clock in the evening, his troops marched through Freiburg and he himself, badly wounded, went with them. They could not stay here either. For Moreau, it is said, is “up to 3 hours from here” and tomorrow the French vanguard will be there.

In Freiburg, which the French occupying troops had left on October 8, people feared a new occupation. Baron von Baden, the President of the Consesses, wrote to the General Command in a moving complaint that the “most devoutly Austrian land of Breisgau”, but especially the city of Freiburg, was already completely exhausted by contributions and wished “ardently” to be protected from new occupation and new mistreatment. He asked for immediate help and provided wagons to transport the troops. But the call for help died away and Freiburg’s fate depended on the military decisions of the next few days.

Meanwhile, Moreau’s intention was carried out exactly according to the plan that had been drawn up. The troops wound their way through the narrow “Valley of Hell” in a long thin line, the march lasted several days, on October 13 the Arriere-Garde had passed Neustadt, and it was not until the 15th that the last troops appeared in front of Freiburg. They had only had a few losses, and an Austrian division under General Merveldt, which had been ordered to follow the enemy “through hell” to Freiburg, certainly did no more harm to them than Colonel d’Aspre’s troops, if the intention was carried out at all. However, Moreau had ordered the baggage and the heavy artillery to take the route via the Waldstätte, i.e. around the southern edge of the Black Forest, towards Hüningen. Thus the French army had happily left the mountains behind them, they were in the Rhine plain and the link with France had been established.

Our story can stop here. For what follows no longer belongs to the episode described here and leads back into the great general war story of the time. We will content ourselves with a few allusions. Both commanders, Morreau and Archduke Charles, were able to realize their strategic ideas. Moreau had crossed the Black Forest and regained the freedom of movement. The Archduke succeeded in drawing his entire force to him and facing the French on the southern front. On October 14, he wrote again to Petrasch: “The main thing is that you must do everything in your power to bring your entire corps together in the Rhine Valley as soon as possible.” A few days later, both armies were ready to fight each other. Through the Battle of Emmendingen on October 19, the Archduke thwarted Moreau’s attempt to break through to the north to dispose of Kehl. And when the French army had crossed the Rhine at Breisach and Hüningen, the campaign of 1796 was over.

A new occupation of Freiburg was no longer to be feared that year. The French, however, tried to conceal the disappointment of their German campaign by glorifying the march through the Höllental. In the Moniteur one read a horrifying description of the dangers of hell and the French historians delighted in the tasteful comparison of Moreau’s retreat with the famous retreat of the ten thousand under Xenophon. Saint-Cyr, however, the true author of this deed, was more honest. “The passage through the Valley of Hell,” he says in his memoirs, “instilled a terror that it did not deserve.”

Leave a Reply