On June 24, 1796, French troops under General Moreau crossed the Rhine at Kehl as part of a three-pronged invasion of the Holy Roman Empire. This came on the heels of an alliance formed by several European powers with the aim of defeating the newly created French Republic. This war is known today as The War of the First Coalition, and it would be the first of several.

Following the first Battle of Kehl, part of Moreau’s army, the southern wing of a larger campaign along the Rhine began a march through “the Höllental,” which translates to Hell’s Valley.

I recently translated passages from Wilhelmiten Kloster Oberried, a history written in 1911 by Fr. Ferdinand Giessler, a priest in Riegel, Germany. The work covers this history of the Wilhelmine monks in Oberried, but the passages I’ve translated highlight the French Invasion, and the subsequent dissolution of monasteries during secularization.

For the descendants of Germans in Baden, this article provides context to the lives of your forbears. The French Revolution and the wars thereafter resulted in tremendous political and social upheaval. If they were unfortunate enough to be along the French army’s route, their towns were ransacked. They were abused and robbed. For Catholics, their churches and monasteries were either burned or taken over by the state and looted. This no doubt left a mark that influenced their lives and the lives of their children.

What follows is the translation:

_______

From the French Wars

In 1789 the terrible revolution had broken out in Paris, the king was executed on October 21, 1793 and the queen on October 16 of the same year. Now Austria, Prussia, Russia, Spain, Portugal, Naples, the Pope and the German Empire formed an alliance to avenge the regicide.

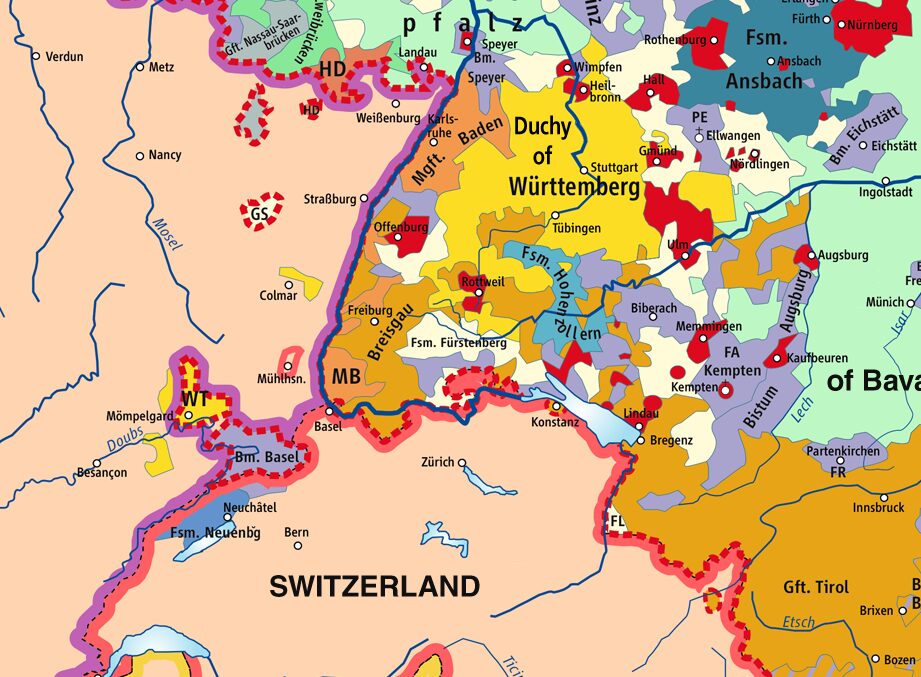

This alliance led to a great war. On June 24, 1796, the revolutionary armies crossed the Rhine at Kehl and advanced towards Breisgau, spreading terror everywhere they went. The so-called Breisgauer Landsturm was organized, which was 32,000 strong and had to retreat at Wagenstadt, Kenzingen and Tutschfelden.

The French, under General Moreau, now marched through the Höllental valley towards the Baar and the Hegau in order to reach the fortress of Ulm. The enemy troops plundered and robbed in the villages and single-layered farms, abused men and women in a terrible manner in order to extort money, and ravished the latter worse than the Swedes had done in the past. The last abbot of St. Peter, Ignaz Speckle, described the outrages that took place in Eschbach in detail in his memoirs.

However, the French did not get any further than Stockach, where they were defeated by the Austrians. Archduke Charles also advanced from Ortenau towards Freiburg. On October 18, small victorious encounters took place near Kenzingen, Malterdingen, Köndringen and Waldkirch, in which Archduke Charles, who was quartered in Riegel, personally intervened.

Now Moreau had to begin his ignominious retreat through the Höllental valley. In the week of the church consecration, 40,000 men marched through the Höllental within three days; they plundered everywhere again, set fire to many places, such as Rötenbach; they also burned down the church in Neustadt. It was fortunate that the enemy had to hurry and did not have time to get far away from the road.

“The retiring Frenchmen’s parade was ridiculous. Most of them had no shoes; they were covered with bed sheets or carpets, some wore peasant smocks, others wore coats of all colors, some were seen in women’s dresses, some in choir skirts, some dressed in chasubles. The whole thing resembled a masquerade.” So writes the chronicler.

That was Moreau’s retreat in 1796, on which the French also came down from the heights through the Weilersbach valley, where the Austrians already met them and engaged them in a small skirmish. The soldiers who died in this battle were buried in a mass grave directly in front of the entrance to the Oberried church. In view of the outrages committed by the French, Mathias Dufner, a miller in Oberried, killed a French surgeon within the monastery walls.

The French wanted to set fire to the monastery because of this, but had to retreat as quickly as possible. During this and the later march through by the French, the monastery suffered a loss of 3400 fl. Moreover, like the monasteries in St. Peter and St. Märgen, it had been converted into a military hospital.

Dissolution of the Monastery and Departure of the Monks

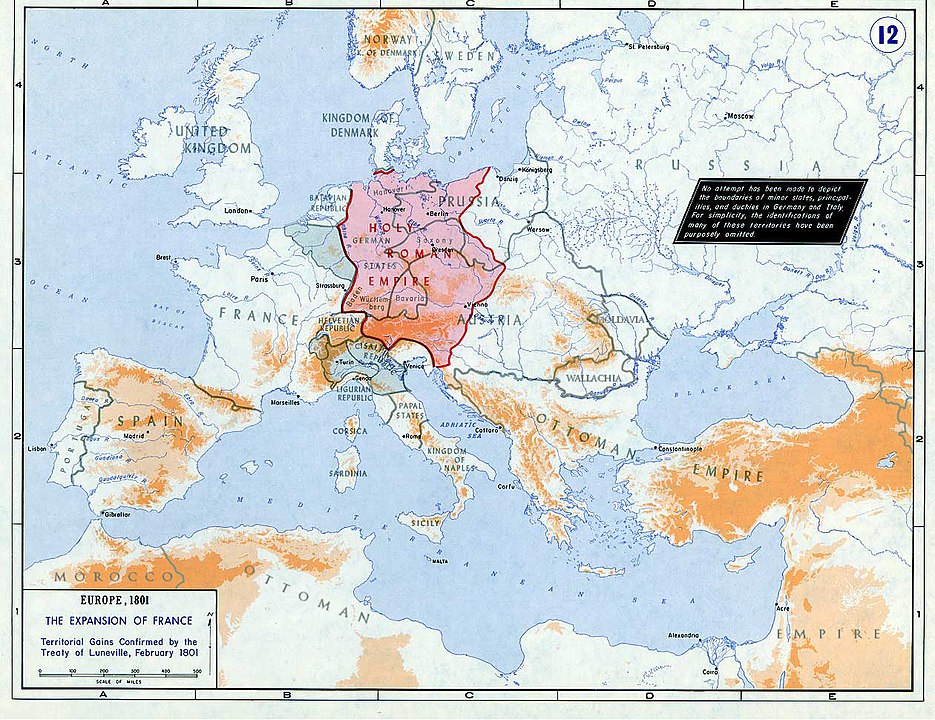

The revolution under its genial upstart Napoleon had risen to bloody struggles and thus brought to bear the principles of ousting the church from its traditional possessions. Austria lay defeated and exhausted and had to agree with everything. There was no longer any question of respecting foreign rights.

The secret treaties of the Peace of Paris (1796), to which Baden only agreed after much hesitation, while Württemberg agreed with a light heart, already contained the main features of the coming development: The southern German princes ceded all their possessions on the left bank of the Rhine to France and in return received the right to secularize the bishoprics, abbeys and monasteries in their lands, which they promised to actively help to carry out.

The same was agreed by Austria in the secret articles of peace, openly proclaimed at the Rastatt Congress, legally sanctioned in the Peace of Luneville (1801) and finally put into practice by the Imperial Deputation at Regensburg. The great country market in Paris was opened. Like a swarm of hungry flies, the German princes and diplomats pounced on the bloody wounds of the fatherland, one seeking to outbid the other in the most devout devotion to Napoleon in order to obtain as much as possible at the great imperial auction.

The abbey’s death sentence had already been pronounced when the imperial process of January 25, 1803 proclaimed that Breisgau would pass to the Duke of Modena, who was related to the Austrian Haufe, while the Grand Prior of the Order of St. John at Heiterscheim would receive the county of Bonndorf, the abbeys and monasteries of St. Blaise, St. Trudpert, Schuttern, St. Peter, Thennenbach and all the founders and monasteries of Breisgau in general.

In order to avert this disaster, the abbot of St. Blaise sent the bailiff Duttlinger to Vienna to ensure that St. Blaise was not removed from the sovereignty of Austria. When the Breisgau was ceremonially handed over to the Duke of Modena on March 2, 1803, St. Blaise retained its existence for the time being.

The unfortunate war of Austria in 1805 sealed the fate of the one German Empire, tore Breisgau away from Austria and divided it between two rulers, the Elector of Baden and the King of Württemberg. It was generally a brilliant move on Napoleon’s part that he knew how to draw his princes ever closer to him: First he lured them to him with promises, then he gave them, not all at once, but bit by bit, to encourage them all the more in the hope of receiving the whole thing later.

Thus he divided Breisgau to the two princes who had pledged their heart and soul to him, Baden and Württemberg. Württemberg received the county of Bonndorf belonging to St. Blaise, the towns of Billingen and Bräunlingen, as well as a part of Breisgau that was to extend from the Schlegelberg to the Molbach. Baden received the remaining part together with the foundations and monasteries previously assigned to the Maltese, including the monastery of St. Blaise.

As a result of misinterpretation of the peace instrument, Württemberg laid claim to a much larger part of Breisgau than it was legally entitled to. This is why the so-called. “Acquisition Commission” from Württemberg appeared on January 12, 1806 in St. Peter, on January 17 in Oberried and on January 18 in St. Blaise to attach the Württemberg coat of arms plates. However, the Baden “Acquisition Commission” followed on its heels and appeared in St. Peter on February 22, in Sölden and St. Ulrich on February 23 and in Oberried on February 24 in order to seize the monastery estates. On April 14, the ceremonial handover of Breisgau to Baden took place, and Elector Karl Friedrich received the dignity of “Grand Duke of Baden”.

During this embarrassing period, the Prince-Abbot of St. Blaise and the Abbot of St. Peter attempted one last step towards salvation – they traveled to Karlsruhe to present all the reasons for the preservation of their divine heirs to the bourgeois court. However, they were unsuccessful.

On November 1, 1806, Charles Frederick made the following decision: “In view of the all too many difficulties in carrying out the modifications under which the two abbeys of St. Blaise and St. Peter had been allowed to continue to exist, he considered it advisable to change his opinion to the effect that these abbeys, like all the others in Breisgau, should now be definitively dissolved as incompatible with the institutions of the sovereign Grand Duchy.”

On February 4, 1807, the Oberried priory was then dissolved by the former St. Blasian-Oberried bailiff Josef Frey as Grand Duchy of Baden commissioner.

_______

Post-Script

If you have ancestors who lived in the former Grand Duchy of Baden, put yourself in their shoes and imagine how painful and frightening these times were. War between France and the rest of Europe continued from 1793 to 1815. Men from Baden would be called on to fight for Napoleon, including the disastrous invasion of Russia.

More articles are on the way! As always, if you have any questions feel free to contact me.

Leave a Reply